In December 2020, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued its “Risk Evaluation for Asbestos, Part I: Chrysotile Asbestos” (“Report”). The EPA concluded that chrysotile asbestos presents an “unreasonable risk of injury to health or the environment.” (see Report, pg. 229). The Report addresses two common uses of chrysotile: (1) removing and replacing sheet gaskets, and (2) removing and replacing brake linings.

On its face, the report seems difficult to navigate. However, a closer look raises challenges to both the science of the report and how its information could be used by defense if a plaintiff relies on it. (There was also a Cohort assessment, but for the purposes of this post, we’ll only look at the information regarding brake linings and gaskets.)

EPA’s Methodology

As a whole, this document is produced by the U.S. government; therefore, it would likely be admissible as evidence under the public record exception of the hearsay rule, likely as an unbiased report. However, to assess the science behind the Report, one must first look at the methodology.

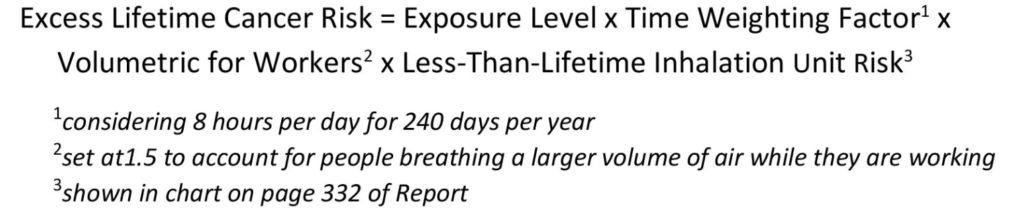

The EPA selected seven studies regarding exposures associated with asbestos-containing brakes (Blake et al. 2003; Cooper et al. 1987; Copper et al. 1988; Godbey et al. 1987; Madl et al. 2008; Sheehy et al. 1987a; and Sheehy et al. 1987b). Using these seven studies, the agency created a median value as the central tendency, short-term exposure level for workers performing brake work (0.006 f/cc). As Beckett, Miller, Peirce, and Finley pointed out during their presentation at 2021 DALS (Defense Asbestos Litigation Seminar), it is not clearly evident how the EPA derived this value of exposures. The EPA did not outline the steps they took to arrive at this number. The Agency defined the short-term exposure value to be that of the “central tendency” eight-hour time-weighted average (TWA) exposure for occupational brake work, assuming 40 brake jobs per week and 8 jobs per day. The EPA also looked at the “high end” eight-hour TWA exposure level, and the sample collected was for 103 minutes during arc grinding of drum brake shoes in both indoor and outdoor environments. In support of this “high end” eight-hour TWA, the EPA selected the highest short-term personal breathing zone result found in the seven studies. In its study, the EPA used this formula to calculate excess lifetime cancer risk:

For brake work, the EPA considered someone performing brake jobs non-stop for 8 hours a day, 5 days a week, 240 days per year. Similarly, for gasket work the EPA considered an individual doing non-stop gasket work for 8 hours a day, 5 days per week, 240 days a year. In short, the EPA used worst-case scenarios to reach their conclusions regarding brake work and gasket work exposures.

Flawed Conclusions

The Report concludes that there is an unreasonable risk to human health from the use of chrysotile asbestos. But how does the EPA define “unreasonable risk”? It’s defined as having the benchmark as greater than 1 in 1,000,000 for the do-it-yourself type exposures and 1 in 10,000 for mechanics. For mechanics, there was less than a 1% lifetime risk of contracting cancer from work-related asbestos exposures. For gasket work, the risk for cancer in an individual performing non-stop gasket work is 5.2 in 10,0000, also less than a 1% risk.

It’s interesting to look at this information in context to other risks included in the National Safety Council’s (NSC) “Odds of Dying.” The NSC chart points out that 1 in 107 people will die from riding in a motor vehicle, 1 in 1,128 from drowning, 1 in 2,535 as a result of choking; and 1 in 8,248 as a result of sunstroke. So according to the EPA, a person has a much higher risk of dying while doing supposedly “safe” activities than from working with asbestos-containing brakes for 40 hours a week, 48 weeks per year, for 40 years. Logically then, the EPA should consider activities like riding in a car or eating to also present an unreasonable risk.

Sources

Beckett, Evan M.; Miller, Eric; Peirce, Jennifer S.; and Finley, Brent. “Comments on the Toxic Substances Control Act Drafted Risk Evaluation for Asbestos Docket No. EPA-HQ-OPPT-2019-0501,” Defense Asbestos Litigation Seminar (2021).

Nadolink, Eric D. “The Baby & The Bathwater: Using the 2020 EPA Risk Evaluation to the Greatest Defense Advantage,” Defense Asbestos Litigation Seminar (2021).

National Safety Council. “Odds of Dying,” 2021.

United States Environmental Protection Agency. Peer Review of the Draft Risk Evaluation of Asbestos. (EPA Document # EPA–HQ–OPPT–2019–0501 (ASBESTOS). June 8-11, 2020.

United States Environmental Protection Agency and United States Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention. Risk Evaluation for Asbestos Part I: Chrysotile Asbestos. (EPA Document #EPA-740-R1-8012). December 2020.